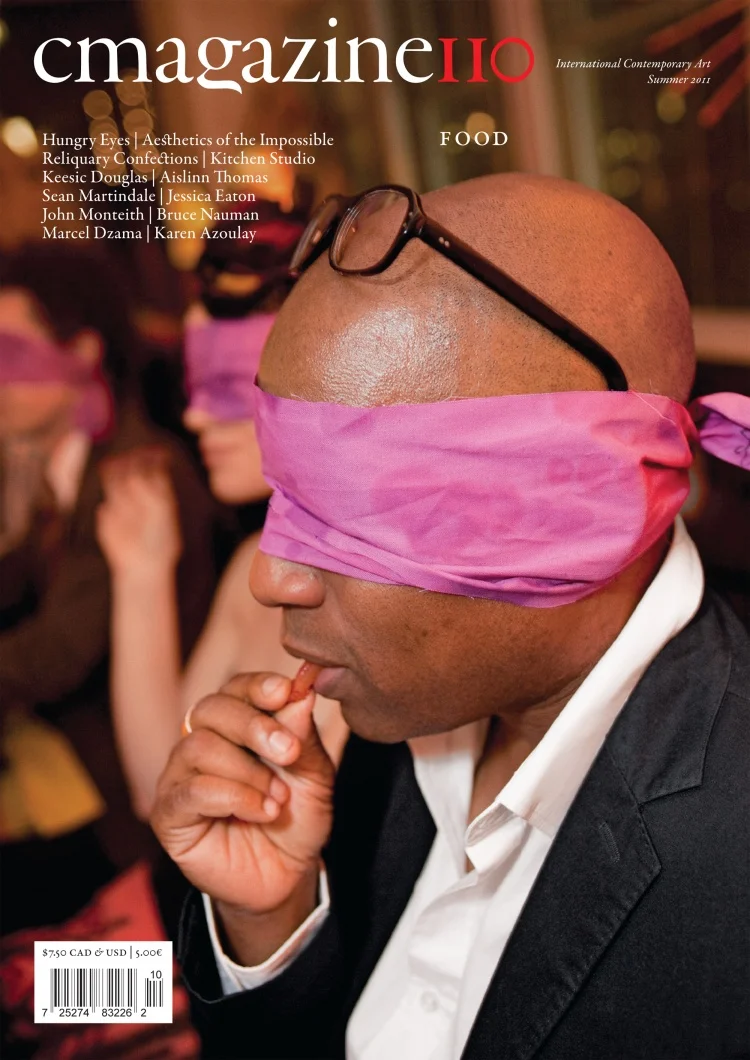

C Magazine Issue 110: Food

Summer 2011

Food

The popular aphorism “you are what you eat” originates with French magistrate, gourmand and author of The Physiology of Taste (1825), Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin.1 In his lengthy meditation on food and the senses, the original phrasing is “Tell me what you eat: I will tell you what you are,” one of 20 aphorisms, most of which are richly reflective of the social values of the time. Fittingly, Brillat-Savarin’s writings helped to not only define gastronomy as an art form, but also to articulate a science of taste, and with it, specific social distinctions. For example, another of the aphorisms reads, “Animals feed: man eats: only the man of intellect knows how to eat.”

Many years later, French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu used methods of quantitative analysis to systematically analyze the relationship between culinary taste and social position. In Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (1979),2 he argues that differences in social class are continually reinforced through aesthetic preferences, and that, in turn, they constitute a form of cultural capital. This is no less entrenched in today’s culture of connoisseurship—built around the popular consumption of celebrity cooking shows and lushly illustrated gastronomic cookbooks—than it was for the social classes of post-revolutionary France. While such social notions of taste can be seen as further cementing existing class structures, taste as a cultivated sensory experience is also a profound and unique source of pleasure and knowledge—and a means of engaging with the world in complex and meaningful ways.

This issue takes a close look at contemporary art practices that engage food as material and as subject matter. In his essay on the food photography documenting creations by chef Ferran Adrià at his now closed restaurant, elBulli—itself included as an off-site project of the 2007 documenta—art historian Mark Clintberg presents a careful consideration of the relationship between the visual and the gustatory senses. Clintberg discusses how images can evoke taste while Liz Linden explains how food can evoke non-gustatory experiences—in this case, fireworks. Karen Azoulay’s recent project Carnation Thunder was an elaborate “conceptual dinner party” performance, during which the artist served smoke-flavoured popsicles and Pop Rocks-infused chocolate, among other edibles. In conversation with Fiona Kinsella, Pandora Syperek also explores the synaesthetic nature of visual encounters with food, as they discuss the artist’s confectionary sculptures incorporating hair, bones and other inorganic materials as decorative elements. Syperek notes that when preserved by icing sugar, these edible forms become like religious relics and the “‘incorruptible’ bodies of saints.” Kinsella observes that we first “eat with our eyes.” Because her cakes are made with hair, bone and teeth, they carry a uniquely disturbing meaning in light of the phrase “you are what you eat,” unsettling the distinction between humans and animals, the living and the dead, and the edible and the inedible—divisions that also play an important role in culture and politics.

Also in this issue, Nicole Caruth explores the disjuncture between images of food and images of disaster in the work of artist Joy Garnett, whose paintings are based on images of military explosions. Discussing Garnett’s project Kitchen Studio (2011), a recipe box that includes dozens of photographs of meals that she prepared, then shared online using Twitter, interspersed with images of her disaster paintings, she looks at how this pairing allows one to consider the gap between a viewer’s experience of images of catastrophe and the events themselves.

Food and food memories form the subject of an artist project by Keesic Douglas reproduced in this issue and titled 4 Reservation Food Group. Including a story describing a recurring dream of the artist’s father, Mark Douglas, this piece reveals some of the complex and unexpected ways that food shapes culture and memory. The food experience described by Keesic and Mark Douglas arises from an experience of poverty – and a history of colonial subjugation by the Canadian government.

However, food can also be restorative. As noted in a recent lecture on artists’ restaurants given by Mark Clintberg, andpresented as part of our educational programming series, “to restore” describes the origin of the word “restaurant.” From about the 16th century to the 19th century, a “restaurant” was a highly condensed, easy-to-digest restorative broth made from cooking and sweating meat until it became a rich bouillon. The modern “restaurant” as a place for private dining—in contrast to inns with their communal tables and limited menus—did not arise until the early 1800s.3 The restorative function of food is evoked through another artist project appearing in this issue. As part of a larger series that includes meals conceived for artists like Thomas Hirschhorn and David Altmejd, Aislinn Thomas proposes a breakfast for British artist Simon Starling. Her menu describes the efficient and sustainable systems of transformation and migration producing the food items chosen for the meal, mirroring many of the structures that Starling reveals in his own practice.

So that we might consider other ideas that are distinct from the theme of food, this issue also includes an essay by Leah Modigliani, exploring topics that arose at the recent conference Traffic: Conceptualism in Canada, held at the University of Toronto. Looking at “impossible” or “imaginary” artworks of conceptualism, and the writing of a history of a conceptual art around such dematerialized practices, Modigliani focuses on a talk by artist and art historian Simon Brown about the work of a group of conceptual artists who apparently lived and worked in Charlotte County, New Brunswick, in the mid-1970s. Swapnaa Tamhane also writes about contemporary performance-based work, but with a focus on India, looking at the work of several artists in relation to traditional forms of performance in that country, and asking whether there might be an Indian performance art movement—and how it might be engaged with regional and national politics.

Across these different critical essays and artist projects is a consideration of how art facilitates a movement between different modes of sensory engagement, such as taste and sight, and between different social and political spaces. But a consideration of food—not just what we eat, but how we eat—both reveals and produces the human subject, making us who we are. Thus, eating is at once a performative act and a way of knowing the world.

Notes

Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, The Physiology of Taste (1825; trans. Anne Drayton, Penguin Books, 1970).

Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (1979, trans. Richard Nice, Harvard UP, 1984).

Rebecca Spang, The Invention of the Restaurant: Paris and Modern Gastronomic Culture(Cambridge MA: Harvard UP, 2000).