See full issue here.

C Magazine Issue 112: Exhibition Practices

Winter 2011-2012

Exhibition Practices

While contemporary art may often appear, for those without specialized training, to be a rarified and hermetic realm—the exclusive domain of artists, critics, curators and collectors—it nonetheless operates as an important ground for intellectual and creative labour with resonance far beyond its own institutions. Art schools, for example, do a great deal more than train artists. If we consider how few art school graduates go on to make a living through art practice, relative to how many make a living through other professions (as set designers, carpenters, architects, film-makers, or writers, or in art-related fields such as arts administration or publishing, for example), we can glimpse the complex and richly generative role that the visual arts play in society. And those without specialized training who visit galleries, attend talks and like to read about, think about, and talk about contemporary art and culture also carry the ideas and experiences they discover into other facets of their lives and work. Contemporary art enables us to reflect on contemporary social and cultural life, and to question some of the ways that we perceive and make meaning in the world—regardless of our profession or depth of involvement. Consequently, the influence and impact of the contemporary art world cannot be measured strictly in terms of exhibitions, reviews or the value of saleable works.

Historically, one major realm of influence of the arts has been social and political countercultures. For example, Courbet, Pissarro and Rimbaud were central actors in the Paris Commune of 1871, and the Situationist International, formed in the late 50s, consisted largely of artists. Similarly, the American counter-culture of the 60s included movements such as Fluxus and the much-reviled “Motherfuckers,” a Dadaist-inspired activist group based in New York City. More recently, artists have turned towards a formal consideration of countercultural social activity and political action. Artists like Mary Kelly, Sharon Hayes and Jeremy Deller, among others, have re-enacted historic political events or forms of protest. And many other artists have created spaces for countercultural communities and alternative channels for the dissemination of critical ideas. For example, in her article that appears in this issue, “New Experiments in Communal Living,” Tatiana Mellema looks at several projects in Canada—including Althea Thauberger’s recent residency, La Commune. The Asylum. Die Bühne., at the Banff Centre in Alberta; Arbour Lake Sghool and The Straw, in Calgary; Don Blanche, near Shelburne, Ontario; and Whitehouse, in Toronto—that have provided artists with alternative spaces for living and work-ing. The opening image for Mellema’s article is a photograph by Thauberger that depicts the residency’s participants posed like the Parisian communards from 1871 standing on the barricades. With everyone positioned across a pile of dirt at a construction site in Banff, its meaning is much more ambiguous, raising questions about our attachment to images and ideals from the past and what contemporary forms of revolutionary protest might look like. In a similar vein, Caroline Seck Langill writes about video artist Tom Sherman and his recent projects focusing on fishing communities along the South Shore of Nova Scotia. This work, much of which is made in collaboration with his partner, biologist Jan Pottie, plays a distinctly activist role, raising awareness about issues related to the fishery and circulating among members of the communities they document through YouTube and Vimeo. In all of these projects, the artists have found ways of working that directly engage the communities with which their work is concerned, and which rely upon alternative structures for production, exhibition and dissemination.

Also in this issue, C examines exhibition practices that facilitate a re-examination of the past in terms of how they orient, or disorient, us in relation to the present. In “A Sea of Contingencies: Durational Projects,” Jesse Birch writes about Sabine Bitter and Helmut Weber’s public artwork A Sign for the City, in which, through a bus-shelter ad campaign and newspaper announcements, the artists link the daily blast of Vancouver’s Nine O’Clock Gun to moments in the city’s history when important social changes were realized. Birch also considers how the first instalment of Cate Rimmer’s three-year-long curatorial project The Voyage, or Three Years at Sea addresses the experience of temporal and spatial disorientation through a focus on the ocean. And, in an interview with Denise Frimer, Robert Houle discusses his recent exhibitions at the Canadian Cultural Centre in Paris and the Art Gallery of Peterborough. Inspired by his encounter with sketches by Delacroix of Native Americans, and accounts that describe the Ojibwa who performed at the court of French king Louis-Philippe in 1845, Houle has produced a number of new works that address the contemporary and historical representation of First Nations people in galleries and museums. Similarly, time and memory are at the centre of Alex Wolfson’s artist project for this issue, which deals with the idea of archives through a philosopher named Fernanda Eva Karon and her lover, Adán Calderón, whose fictional story is the re-enactment of the myth of Tancred and Clorinda.

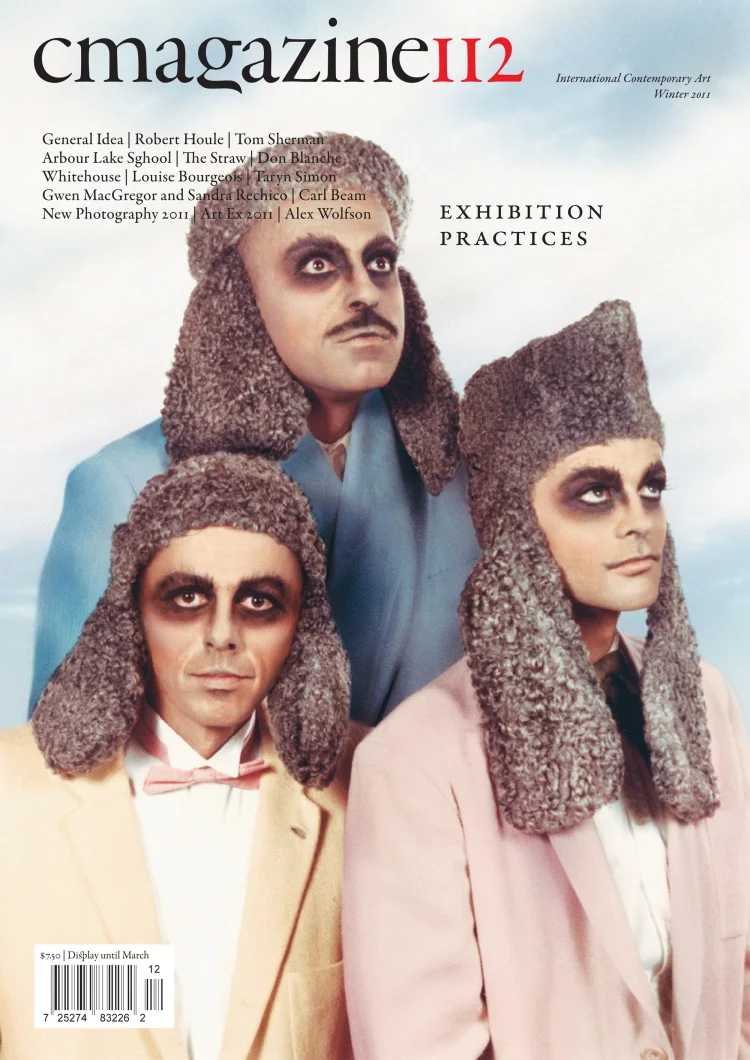

Finally, Philip Monk responds to the General Idea retrospective currently on view at the Art Gallery of Ontario. The collective consisting of Felix Partz, Jorge Zontal and AA Bronson, who worked together from the late 60s until the early 90s, employed strategies of appropriation and myth-making, producing a massive and politically charged body of work that often explored notions of celebrity and glamour, and engaged critically with conceptions of the artist’s identity. For example, in 1987, they appropriated the colours and visual style of Robert Indiana’s 1967 LOVE image, widely reproduced on posters, stamps and greeting cards, re-worked it to read AIDS and then disseminated it around the world as an “image-virus” through posters, billboards and stamps. The image that appears on the cover of this issue, appropriated from the cover of a 1983 issue of FILEMagazine follows on certain elements of GI’s practice and depicts the collective’s three members in poodle wigs. (The retrospective’s curator, Frédéric Bonnet, notes that the poodle—showy and sophisticated, yet banal—appears as a stand-in for a glamorous ideal of the artist’s identity.)1 In his article, Monk explores the idea of myth as a central principle of General Idea’s practice and argues persuasively how, almost twenty years after the deaths of Felix and Jorge, their work has only continued to gain contemporary relevance.

Many of the projects featured herein explore alternatives to traditional exhibitions, and all of them engage ideas that—however elusive they may seem at times—by no means belong exclusively to the art world. In doing so, they enable us to think more expansively about art’s role and value in society.

Notes

- Frédéric Bonnet, “Setting the Stage: Back to Reality!,” in General Idea (jrp Ringer, Zurich, 2011), 20.