View full issue here.

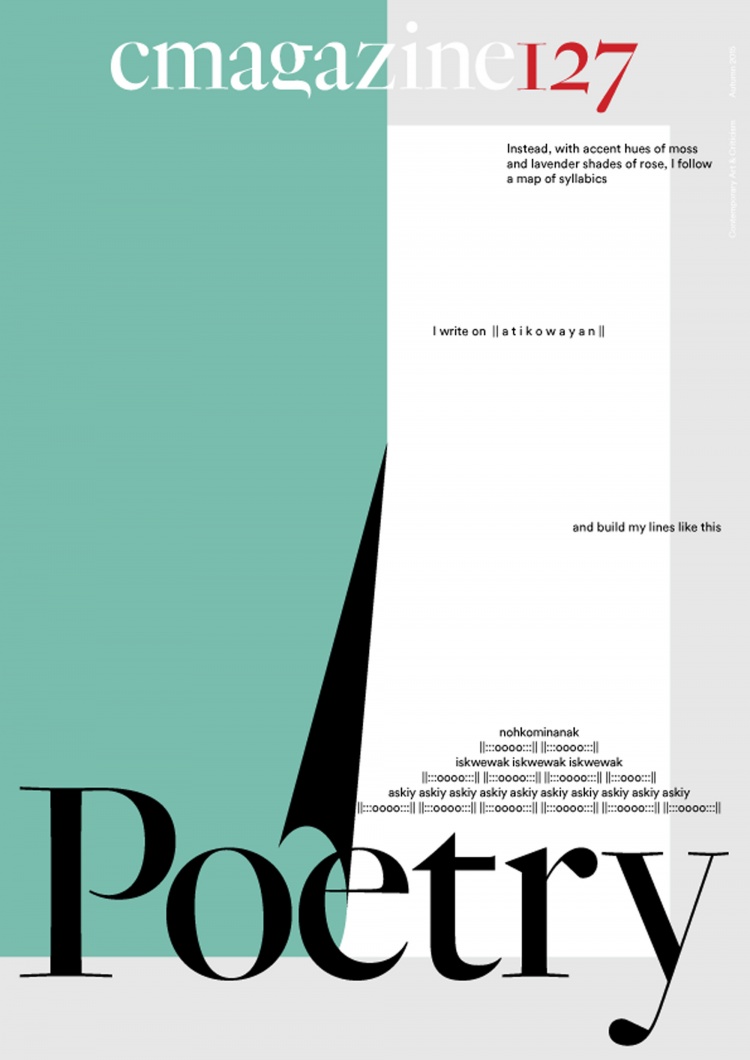

C Magazine Issue 127: Poetry

Fall 2015

Poetry

Amish Morrell: One of the things that defines C Magazine, and which differentiates it from other publications, is the way it plays host to very distinctive, and often divergent voices. We encourage formal and stylistic experimentation among our contributors, which produces enormous variation in how ideas and artworks are presented. This allows contributors to present their ideas in very specific ways that don’t collapse into a general viewpoint or uniform style of the magazine. Among the other potentials of C is that we have a great deal of latitude to experiment with the methods and processes of producing the magazine itself. In response to solitary editorial working practices, I’m interested in making our editorial processes more collaborative and more dialogical, and introducing conditions that shift the content and style of the magazine.

In this spirit, I’ve enlisted some of the people who have been involved with C in recent years – Kari Cwynar, Danielle St-Amour and cheyanne turions – to guest edit an issue on poetry. Together they’ve created an extraordinary issue, where artists and writers explore the intersections of visual art and writing, challenging and advancing formal methods and addressing political forces that are at play in language-based art.

cheyanne turions: I once heard my friend CAConrad say,“I don’t want to write poetry, I want to be poetry.” And I feel like what I would like to do is to be an instrument of poetry, a servant of poetry. What I understand poetry to be is the practice in which we cultivate and serve and protect our sociality by constantly changing it, by constantly disrupting it and improvising upon it. And I would like to be an instrument of that, a participant, so to speak, in that practice. Fred Moten, in interview with Housten Donham

A many-pointed constellation took shape in the production of this issue: labour and care arising amongst Kari, Danielle and I as guest editors, in dialogue with a cast of writers through their urgent subjects, encouraged by the infrastructure of C Magazine. Throughout these pages, there are all kinds of support structures, bolstered by challenges made and taken (the delicate dance of listening made flesh). If there is a burgeoning collectivity that the voices in this issue conjure, I would like to think that it first took root in how this issue was made.

The conceit that poetry and visual culture are separate genres is repeatedly undone throughout these pages. This is not to say that they converge into a hyphenated or hybrid style, but that the agency embedded in the world of appearances, alongside the strange compositional possibilities of language, marks a specific strategy that renders visible a politics of world-making. Perhaps not always, and perhaps sometimes used to deleterious effect, but here, throughout these pages, the confluence of poetry and visual culture operates as a critique of how meaning is constructed. What arises is the imperative to interrogate one’s participation in systems that otherwise work to make themselves invisible. Consider Fan Wu’s call to afford comparable material and intellectual weight to source-language and target-language in acts of translation; or Lucy Ives’ simultaneous desire for and experimentation in creating a temporally specific reader through writing; or Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s use of equivalencies to recast the world in a whisper. There is a momentum here, taking us elsewhere.

“All in all, the poem protests, and for the poem there is the protest that refuses the separation between language and life…a poem doesn’t tell. It makes.”2

Kari Cwynar: I’ve been the Assistant Editor of C since January 2015, which includes the responsibility of assessing pertinent themes in art writing and criticism for upcoming issues. Poetry was an immediate choice, not only as a genre I often turn to, but as one with an important and evolving relationship to the art world. Danielle and cheyanne came forward at the same time with similar investments. We discussed hybrid artist-poets, material poetry, poetic press releases and artist talks, the idea of “trend.” We looked back to precedents, unwilling to see the art world’s current interest in poetry as new, but as a lineage. But we always returned to the politics and performativity of poetry – the essential thing that poetry can do as form, what it can offer writers, thinkers, artists and activists, its availability as a mode in which to enact life. It’s a tenuous statement, to decide that one form offers more political affect than another, but read Nasrin Himada’s contribution to the issue, on poetry, resistance and the body, or Rachel Valinsky’s close reading of a series of works by Gins and Arakawa, who used poetry as means to further their radical politics around the reversibility of life and death: the refusal to die. Read poet and artist Olivia Dunbar’s review of the exhibition Them at the Schinkel Pavillon and consider a candid, unbridled poetic voice, one that sheds the posturing of art criticism as such.

What I see most in assessing the current relationship of art and poetry is the sense of a group of thinkers looking outside artistic and literary conventions and more significantly beyond the status quo of civic life. It is in poetry where readers and writers actively reject Kenneth Goldsmith’s “remix” of Michael Brown’s autopsy report or Vanessa Place’s adoption of the voice of Mammy from Gone with the Wind. Poetry is a form that cultivates its readership, and constantly re-negotiates positions and subjectivities.

Danielle St-Amour: In April of 2012, Lisa Robertson gave a talk at Concordia University called “Risking Rhythm.” In her talk, Robertson considers the Saussurean division of language into “signifie” and “signified,” naming it as the “definitive gesture of 20th-century intellectual methodology.” This dual nature, she argues, is a cornerstone in the methodology of a surveillant, codifying system. It is through the instrumentalization of this division, she states, that bodies are separated from agency, as materiality is separated from meaning.

“Against all poeticizations, I say there is a poem only if a shape of life transforms a shape of language and if reciprocally a shape of language transforms a shape of life.”1

Through conversation around this issue, we agreed that the most engaging proposition of poetry was its ability to both engage and enact life. We sought work where we saw the sensorial and the physical combining to make new spaces; new bodies reforming material and meaning. We endeavoured to include those who make life of poems (CAConrad); make words and histories recombinant (Robertson and Doris); coalesce language, form and body (Lippard, Lukin Linklater, La Melia, Turgeon); and use prose as radical material (Himada). With hopes that language, here, is granted status as both the method and the main business, with reverence to its possibilities and its slippages.